The Value of the Natural World

The word value has as many meanings as there are humans that contemplate any value consideration. Unfortunately, the arguments on the table today over the value of the interrelations of the natural world, animate and inanimate, are being defined by human intellect without regard for consequence. This should not be. Nature’s interrelations are not of our making. We know nature’s value is an arcane formula not based on human rights or personal predilection. It is what it is, but what it is has not been revealed with certainty by known science.

Nonetheless, the arguments among what has become known as the ‘stakeholders,’ those that profit and benefit from the natural world, all stand on the same base: nature as humans’ chattel. Before it is too late to do anything else but ‘play it as it lays,’ we need to pause and contemplate how we arrived at our current view of Earth and our place in its landscape. Mankind’s art may be a clue.

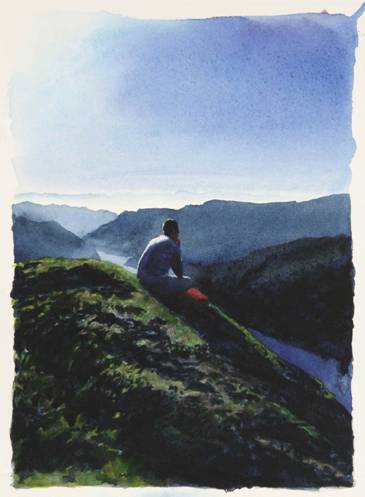

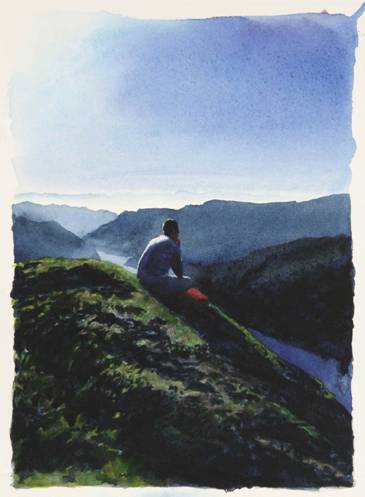

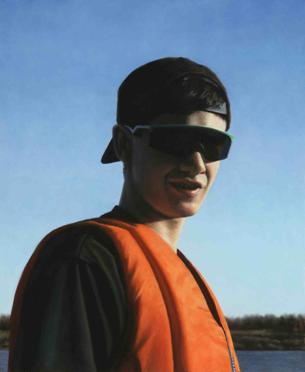

Canadian artist Tim Gardner uses photographs to fuel his artistic view of man in nature. Depicted above is his bother Tobi contemplating a vast wilderness landscape. In an Apr. 28, 2000 issue of Columbia University’s publication Record, the recent Master of Fine Arts graduate was recognized as having achieved a success not often accorded an artist choosing water color as their major medium of expression.

“Tim Gardner . . . has arrived, " Jason Hollander, the reporter, decreed in this now over ten year old story, adding that Gardner took the New York art scene “by storm.”

The reporter painted his own verbal picture to explain the artist’s rapid ascension: talent. He quoted Gardner’s mentor and teacher Archie Rand, Chairman of Columbia’s Visual Arts Division to explain Gardner’s work:

The reporter painted his own verbal picture to explain the artist’s rapid ascension: talent. He quoted Gardner’s mentor and teacher Archie Rand, Chairman of Columbia’s Visual Arts Division to explain Gardner’s work:

"I took one look at his work and said to myself: This guy gets it. He's not making art that is answering academic or verbal questions. He's making works of necessity. I realized what I was looking at was enclosed narrative, not just situations. Tim's skill elucidates, rather than masks, his personal concerns. His confidence becomes a display of intelligence."

If one were to take a pair of scissors and cut Gardner's work of his brother Tobi into pieces and scatter them, randomly, on a table for our review, we would have a Picasso-like deconstructionist’s view of a landscape, not Gardner’s. His clear, lucid, snapshot-truism of the value of man’s place in nature would be gone.

Neil Carter, the author of the book The Politics of the Environment: Ideas, Activism. Policy, labours over the visual value statement Gardner defines with his art. Carter devotes twenty pages to the deconstruction of the word value, a theme, he says, has evolved among “stakeholders” in decision-making conflicts over environmental issues. Disparate views of value, between stakeholders result in “value eclecticism,” he explains. Carter’s deconstruction of the word value leaves it un-whole, conspiring against his own personal holistic theory of nature. The label Carter applies to the politicisation of nature’s value becomes “the traditional policy paradigm.” He fears it is masking environmental concerns and delaying choices. As a result of his efforts Carter allows himself to become entrapped, answering the “academic” and “verbal” questions that Tim Gardner’s art escapes. Holism is the statement in Gardner’s work of art. His whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It goes beyond greater. It is subtlety yet significantly different. In the Richard Foltz anthology of articles written on the subject of man’s place in nature: Worldviews, Religion, and the Environment, he includes an excerpt from a book by historian Carolyn Merchant. The chapter ‘Dominion over Nature,’ from her book The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution, tells us where our current view of man’s relation to nature came from: Francis Bacon.

Bacon, Merchant reminds us, took the momentum of the Enlightenment period and moulded it: “. . . into a total program advocating the control of nature for human benefit. Melding together a new philosophy based on natural magic as a technique for manipulating nature, the technologies of mining and metallurgy, the emerging concept of progress and a particular structure of family and state, Bacon fashioned a new ethic sanctioning the exploitation of nature.”

There’s more. Merchant gives us a history lesson: Bacon was the first person to fashion environmental legislation. He had King James I pass laws outlawing the female witch and toughen penalties for the practice of witchcraft in nature to include torture and death. Bacon then replaced the subjugated, violated, tortured, female witch with the exalted male magician, resulting in what Merchant calls the Baconian Program, whereby she says: “The new image of nature as female, to be controlled and dissected through experiment, legitimated the exploitation of natural resources.”

Bacon wrote of a prescribed research institution, Salomon House, a vision of a utopian island in his work, New Atlantis. Named for the Hebrew King, its mythical creation later began the dissection of nature, and we learn from Merchant we should credit Bacon’s Salomon House vision to the emergence of modern day scientific research institutes and scientific methods. Secretive operation sanctioned the hoarding of information on both Salomon House experiments and their results.

It is no coincidence that the ascension of Pablo Picasso and other artists of the period of ‘deconstructionist art’ mime the deconstruction of nature. It began with Francis Bacon, and it culminated in the industrial revolution. The fastest progress of technology the world had then known peaked during the time of Picasso and his contemporaries’ acclaim. These artists validated the prevalent male view of those times: how we stand in our world against — and triumph over — nature. All great artists have been in sync with their times. The public gives them acclaim based on a perception of the work’s relevance and value to their generational milieu.

It is no coincidence that the ascension of Pablo Picasso and other artists of the period of ‘deconstructionist art’ mime the deconstruction of nature. It began with Francis Bacon, and it culminated in the industrial revolution. The fastest progress of technology the world had then known peaked during the time of Picasso and his contemporaries’ acclaim. These artists validated the prevalent male view of those times: how we stand in our world against — and triumph over — nature. All great artists have been in sync with their times. The public gives them acclaim based on a perception of the work’s relevance and value to their generational milieu.

Our current view of the value of nature has brought us to the precipice of what another female contributor to Richard Foltz’s anthology, Australian, aboriginal Mary Graham, calls: ". . . belief without reflection,” which brings us back to Tim Gardner and his fluid water colors depicting man in nature. His instant success within the environs of the World’s largest shrine to the male view of “Dominion over Nature,” New York City, gives us hope that reflection by the male established view of nature — and its value — is in progress, albeit silent progress — clearly not yet self evident.

Our current view of the value of nature has brought us to the precipice of what another female contributor to Richard Foltz’s anthology, Australian, aboriginal Mary Graham, calls: ". . . belief without reflection,” which brings us back to Tim Gardner and his fluid water colors depicting man in nature. His instant success within the environs of the World’s largest shrine to the male view of “Dominion over Nature,” New York City, gives us hope that reflection by the male established view of nature — and its value — is in progress, albeit silent progress — clearly not yet self evident.

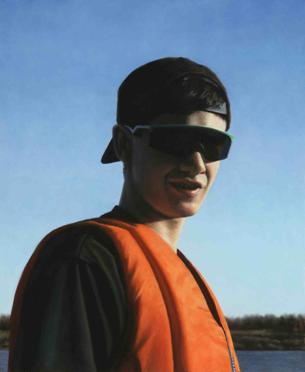

Gardner’s work is almost exclusively about males. “Women come and go,” one art critic noticed. Gardner has a very masculine theme. Males are embracing his art. Gardner’s appeal is a reflective male attitude, and we learn from the Guggenheim curatorial comments he accomplishes his goals by exploring “a specifically North American middle-class world of masculinity and the photographic conventions used to document it.”

The Guggenheim explains why Gardner’s depiction of the male psyche is different: Despite the good time theme, the male expressions are “markedly self conscious and troubled,” with “stilted gazes.” The expected expression of male bravado or camaraderie is missing, according to their comments on his work, and his work, says the Guggenheim, describing Gardner’s depictions of his brother in nature’s backdrop, “incites a new vein in the artist’s engagement with male identity as one less inclined to grandiose reverie, as he settles into a nonchalant pose before expansive mountain ranges and glorious skies.”

The museum points to a close up of Tobi, in another Gardner work, where the subject, not the landscape, predominates. In their commentary on Gardner’s ‘Tobi, on the Red River,’ they say: “Gardner deepened his investigation of nature, revealing, through personal as well as advertising photographs, the “wilderness” to be a site as mediated and constructed as masculinity itself.”

The value of the natural world is its significance; its significance is its ability to sustain each and every living and non living thing on the planet. The human element that does have stewardship over the planet and commands the sum of the value parts has little margin for error if they do not deciphers its interrelations first.

The acceptance by the art world of Gardner’s chosen mediums, water color and pastel, as ones that can now be viewed as capable of equality with the medium of oil, documents a new realization of the nature of the planet and any individual’s context on Earth. It is ephemeral and transient.

A question Carter poses: Does nature have value independent of our needs assumes there is a possibility we are not dependant on all of nature. Science has taken us far enough to give us an inkling that nature’s holistic value is a truism; we ignore our instincts at our own peril; therefore, no part of nature is more valuable than others; we need it all.

There need be no duties to nature if this is understood, only stewardship, and if we understand how we got to our view of the natural world, a Baconian view of nature as man’s slave, to be pounded on an anvil, we then we can put nature conceptually back together.

Government leaders view contemporary environmental problems as complex because they weigh the information provided by scientists against the weight of the stakeholders in play. The accepted practice is reliance on the scientific expert, without verification of facts. This makes certain the scientists are not questioned.

Carolyn Merchant’s ‘Dominion over Nature,’ blames Baconism for the lasting influence on the way nature has been, and still is, treated. Describing Bacon’s scientific research institute, Salomon House, she says: “… politics was replaced by scientific administration. Decisions were made for the good of the whole by scientists, whose judgment was to be trusted implicitly . . . . Scientists decided which secrets were to be revealed to the state as a whole and which were to remain the private property of the institute rather than becoming public knowledge.”

Merchant says England’s Royal Society took on the Baconian philosophy of the Salomon House role. In its modernity, business has created hundreds of Salomon House clones, the ‘research institute’ adept at manipulating scientific information and policy. The result, according to Canadian Neil Carter, is the evolution of today’s ‘policy communities,’ exhibiting: “a closed stable membership, usually involving a government ministry or agency and a handful of privileged producer groups, who regularly interact and share a consensus of values and predispositions, almost a shared ideology about that policy sector that sets the community apart from outsider groups,”

Carolyn Merchant blames Baconian evolution to a view of nature as female for its dissection and exploitation. Noting her chosen quote from Bacon’s work The Masculine Birth of Time: “I am come in very truth leading you to nature with all her children to bind her to your service and make her your slave,” we can see an entrenched, male view of our planet. It must change before change in Neil Carter’s entrenched policy paradigm can come about.

Picasso era art imitated the Baconian view of Earth as dissectible. Tim Gardner’s work is evoking male reflection. Jerry Saltz, an art critic for the Village Voice commented on the bottom line of Gardner’s work: “For some, genesis is a point of departure. For others, like Gardner, it is the subject.” What can we envision that will bring about a new masculine view of leadership that includes reflection when contemplating use of the natural world’s resources?

Envision some formidable, male steer, a mighty “Tobi”; he pulls his gun; raises his hoof to the sky; fires to the heavens; and calculatingly and coolly issues the imperative command to the world’s male herd: STAMPEDE!

ART CREDITS

Tim Gardner

Tobin in a Landscape, 2006

Watercolour

Work on paper

8 1/2 x 7 1/4 inches (21.6 x 18.4 cm)

Burger COLLECTION, Zurich

Courtesy of the artist, through the 303 Gallery, New York.

Tim Gardner

Tobi on the Red River, 2006

Pastel on Paper, mounted on canvas

34 x 28 inches (86.4 x 71.1 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Purchased with funds contributed by Ann and Steven Ames, with the support of the artist and 303 Gallery, 2007

20007.3

Pablo Picasso

Landscape at Céret (Paysage at Céret), summer, 1911

Oil on canvas

25 5/8 x 19 ¾ inches (65.1 x 50.3 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, By Gift

37,538

TG 350 TIM GARDNER

Untitled (Tobi in the Landscape)

2006

Watercolor on paper

8 1/2 x 7 1/4 inches (21.6 x 18.4 cm)

16 x 14 3/4 inches (40.6 x 37.5 cm) framed

The reporter painted his own verbal picture to explain the artist’s rapid ascension: talent. He quoted Gardner’s mentor and teacher Archie Rand, Chairman of Columbia’s Visual Arts Division to explain Gardner’s work:

The reporter painted his own verbal picture to explain the artist’s rapid ascension: talent. He quoted Gardner’s mentor and teacher Archie Rand, Chairman of Columbia’s Visual Arts Division to explain Gardner’s work:  It is no coincidence that the ascension of Pablo Picasso and other artists of the period of ‘deconstructionist art’ mime the deconstruction of nature. It began with Francis Bacon, and it culminated in the industrial revolution. The fastest progress of technology the world had then known peaked during the time of Picasso and his contemporaries’ acclaim. These artists validated the prevalent male view of those times: how we stand in our world against — and triumph over — nature. All great artists have been in sync with their times. The public gives them acclaim based on a perception of the work’s relevance and value to their generational milieu.

It is no coincidence that the ascension of Pablo Picasso and other artists of the period of ‘deconstructionist art’ mime the deconstruction of nature. It began with Francis Bacon, and it culminated in the industrial revolution. The fastest progress of technology the world had then known peaked during the time of Picasso and his contemporaries’ acclaim. These artists validated the prevalent male view of those times: how we stand in our world against — and triumph over — nature. All great artists have been in sync with their times. The public gives them acclaim based on a perception of the work’s relevance and value to their generational milieu. Our current view of the value of nature has brought us to the precipice of what another female contributor to Richard Foltz’s anthology, Australian, aboriginal Mary Graham, calls: ". . . belief without reflection,” which brings us back to Tim Gardner and his fluid water colors depicting man in nature. His instant success within the environs of the World’s largest shrine to the male view of “Dominion over Nature,” New York City, gives us hope that reflection by the male established view of nature — and its value — is in progress, albeit silent progress — clearly not yet self evident.

Our current view of the value of nature has brought us to the precipice of what another female contributor to Richard Foltz’s anthology, Australian, aboriginal Mary Graham, calls: ". . . belief without reflection,” which brings us back to Tim Gardner and his fluid water colors depicting man in nature. His instant success within the environs of the World’s largest shrine to the male view of “Dominion over Nature,” New York City, gives us hope that reflection by the male established view of nature — and its value — is in progress, albeit silent progress — clearly not yet self evident.